Next in our series, Rooted in Resilience: From Crisis to Opportunity, is the story of how farm families grappling with hunger in a dry region of Africa came up with a way to improve their food security, and how that innovation spread throughout Mozambique. For more photos and stories, please download our 2013 annual report.

A big challenge faced by farmers worldwide is uneven seed quality. When many seeds fail to grow, it means poor yields and a food gap from one harvest to the next. Getting quality seed is a serious problem in the dry Cabo Delgado region of northern Mozambique, where more than half of all households suffer severe food insecurity.

Cruelly, in Cabo Delgado the shortages hit worst in the months just before the next harvest. Many people call February “the most dangerous month.” That’s when they go to bed hungry.

“Lack of food, for us,” said one mother of young children in Pithola, means “no food inside the house, so you go to another village and look for work. Or you even take your clothes and give them to someone in exchange for food.”

Amplifying the risks of that dangerous month, in February 2013 there was a cholera outbreak in the districts of Cabo Delgado where the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) works.

To tackle the problem, AKF piloted a new way for farmers to select and store seeds. The project helped farmers systematically choose heartier seeds to plant next season, with an inexpensive technique for storing seeds better. For this Seed Systems Actions in Cabo Delgado (SSAC) project, AKF partnered with the Eduardo Mondlane University and the country’s Ministry of Agriculture.

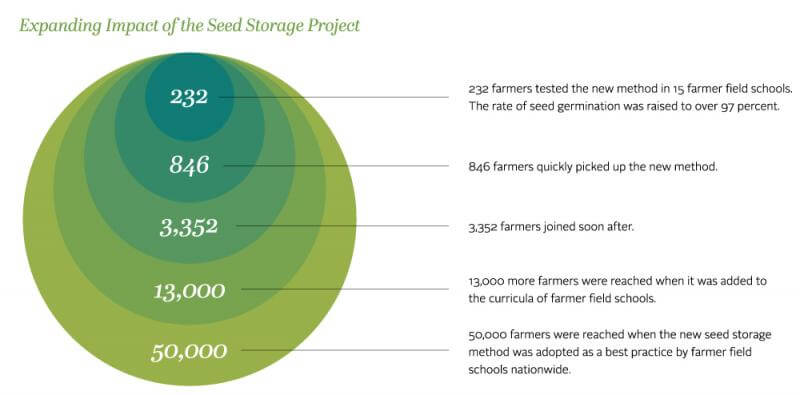

Farmers (almost half of them women) tested the new method and discovered it yielded much higher success rates: over 97 percent germination for maize and beans after eight months of storage, compared to under 80 percent before the pilot.

The method is simple enough for anyone to use. Farmers place seeds in plastic bottles with ash to minimize air contact, and then put the bottles in a cool box made with bamboo and mud (both local materials) for temperature control. The method protects seeds from insect and rodent damage, moisture, and high temperatures.

Success spread quickly. The new method became part of the curriculum for Farmer Field Schools across five districts and soon reached over 13,000 farmers. Each farmer trained in the method, in turn, trained another four farmers. Women in particular embraced the improved method and enthusiastically shared it with other women. A vital ingredient of their resilience in this difficult region is openness to innovation.

Beyond Cabo Delgado, the pilot spread much farther than anticipated at the outset. At a national-level meeting in the capital, the Ministry of Agriculture adopted the SSAC method for use in all of its farmer field schools, reaching 50,000 farmers nationwide. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations also embraced the method. This exciting development ensures that the success that started in a local pilot effort will improve the food self-sufficiency of farmers across Mozambique for many years and harvests to come.

For more about AKF’s programs, download the 2013 AKF USA annual report. Check out the full Rooted in Resilience: From Crisis to Opportunity series here, and be sure to join us on Facebook!