This is the first in our series, In Pursuit of Good Governance, with stories from our new annual report. The four-part series examines a question that our partners face every day: How do communities access and organize basic services to ensure a better quality of life? Reliable hospitals, schools and community centers. Flourishing economies. These are cornerstones of all healthy communities that allow people to gain the collective power to shape their futures.

The stories in this series offer snapshots of how the Aga Khan Foundation and our partners address that challenge– within a community, within a district, and across borders. We start with schools in two communities faced with scarce resources, but a wealth of commitment.

In Remote Communities

A teacher like Ms. Perris Mwapheku is willing, even after 25 years, to try a new method for teaching reading if research has proven that it works.

“I am open to new challenges,” said Ms. Perris Mwapheku, a 3rd grade teacher in Kenya’s remote Kwale County. Although near retirement, she embraced new methods she learned with the Education for Marginalized Children in Kenya (EMACK) program. “I saw it as an opportunity to help my students.”

Families in Kwale County, at Kenya’s southern tip, live at the margins. Less than half have basic sanitation and only 5 percent of the roads are paved. Despite these limitations in their lives, parents engaged with whole school improvement to support teachers and students. For a family to get involved in their school is a vote of hope.

Aga Khan Foundation’s (AKF) long-term approach to improving schools engages an entire community in creating workable solutions. The process – called the whole school approach — combines the energies of parents, educators, school management committees and the wider community, along with teachers and pupils to participate in children’s learning processes, develop a community of reading, and identify school challenges and solutions.

EMACK focuses on education for groups often overlooked. Funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and Aga Khan Foundation, EMACK has extended AKF’s experience in East Africa and deepened its commitment to children’s early years of learning. Begun in 2006, the program evolved along with Kenya’s education environment to address overcrowded schools, and a need for improved learning outcomes. In eight years, EMACK improved school opportunities for 500,000 children in 935 pre-primary and primary schools across three regions (Coastal Province, Northeast Province and Nairobi). Nearly half the student’s impacted were girls.

Teachers like Ms. Perris work in remote districts and squatter settlements with few formal structures. EMACK worked with local governments to provide in-school mentoring for over 3,450 teachers. To create supportive teaching networks, cluster meetings provided opportunities for teachers from 3-5 neighboring schools to meet regularly for shared learning.

Ms. Perris engaged her students with reading in new ways, creating charts and posters that made her classroom walls speak to the students. Alongside “talking walls,” she also started a mini-library with EMACK support, which encourages children to take books home and share reading with their families. With training in the Reading to Learn approach from EMACK, she sees improved results. Reading to Learn starts from the child’s context; builds on stories that have been told at home; and teachers encourage students to talk about their own stories, while linking those to lessons.

After implementing new techniques, Ms. Perris reported that over 80 percent of her students can read fluently and with good comprehension—well above the average for students in Kwale (65% for female students, 48% for male).

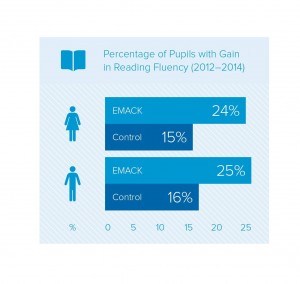

Kenya’s education system has absorbed many EMACK elements after school visits by officials showed the methods at work. In the coastal city of Mombasa, the county education strategy includes scaling up activities begun under EMACK including in-service teacher training and increased parental involvement. In remote Garissa County, officials saw that pupils in EMACK schools acquired better reading skills than students in non-target schools.

Besides improving student performance, the whole school approach helps communities see a bigger picture. Communities learn how making decisions collectively can improve the quality of life for all their families. As EMACK concluded in 2014, the Kenyan government adopted the whole school approach for 3,600 primary schools nationwide and committed to supporting children in a comprehensive way.

View the photo series about EMACK’s impact on a primary school in Mombasa here.